It goes without saying that Satan has fascinated humanity since… well, a very long time indeed. Representations of evil predate Christianity’s version by millennia, and some devils are consequently heavily inspired by pre-Christian tradition. The most fascinating aspect of him is probably that there are so many variations. But what are the coolest most haunting representations of Satan in literature?

From simple two-dimensional portrayals of absolute evil to highly complex characters with confusing motivations, representations of the devil in literature are as varied as they are many. It just goes to show how pre-occupied humans are with the idea of evil and temptation, and what characteristics we believe best represent pure evil.

If you move away from straight-forward portrayals of Satan, things become even more confused. Captain Ahab and/or Moby Dick can be read as versions of the devil himself; Sauron or Lord Voldemort come close to being Satanic manifestations; even in less fantastical literature – such as much of Dostoevsky’s work – we can find figures who could be said to be ‘of the devil’s party’.

Consequently, when selecting my list for a few examples of fascinating ‘Satans’, I had to limit myself drastically. I will only list figures who are actually the devil, not Satan-like characters. But even then there are countless options to choose from, and all vary.

Additionally, I will also just pick some of my favourite representations. You could write endless essays on any given of these characters, so rather than doing an ongoing list with no descriptions, I thought I’d focus on just a few of my favourites to give you a quick taster, in the hope that you may find it interesting. There are, doubtlessly, many, many other Satans out there which you may find equally or more engaging than the ones I’ve chosen. So! Without further ado, here it goes.

Dante’s Three-Headed Satan

In Dante’s Inferno from the Divine Comedy, Virgil leads the poet through the circles of hell on their path to purgatory. On the way, they must brave some of the most horrific things imaginable, with each of the nine circles representing an individual sin – lust, gluttony, greed, wrath, heresy, violence, fraud and treachery.

Unlike some of the other representations, this Satan is passive. Having committed treachery to the Christian God, he is condemned to the very centre of the ninth and innermost circle of hell, where he is frozen waist-deep in ice and suffering eternally.

On top of that, Dante’s Satan has three heads which are constantly crying a mix of blood and pus. Each mouth is perpetually chewing on some of history’s great traitors – two murderers of Caesar and Judas Iscariot. Overall, it’s a pure depiction of absolute misery.

Dante’s hell is primarily a warning to wrong-doers: commit one of these sins, and you will end up here and suffer in this way. Treachery is by far the worst sin and woe be you if you are found guilty of it. No wonder this still remains one of the most popular depictions of Satan to this day.

Milton’s Fallen Hero

My personal favourite representation, Satan in Milton’s Paradise Lost is primarily a figure fallen from grace. Of course, Dante’s version is also the ex-archangel Lucifer, but here we get the full story and Satan’s gradual fall into slime, muck, and all that’s bad.

My personal favourite representation, Satan in Milton’s Paradise Lost is primarily a figure fallen from grace. Of course, Dante’s version is also the ex-archangel Lucifer, but here we get the full story and Satan’s gradual fall into slime, muck, and all that’s bad.

Also, this Satan is far more active. After losing the battle against the heavens, God bans Satan to hell where he rules over his own kingdom. And at first he still maintains his glory and his honourable appearance. Only as the poem goes on does he gradually become deformed, twisted, malicious.

Added to that, Satan is by far the most eloquent character in the poem. He convinces Eve to eat the fruit from the tree of knowledge, after all. Milton cleverly depicts how Satan’s rhetoric gradually becomes more flawed and full of inconsistencies as he develops, in the same way that he starts out as a fallen angel and ends up appearing as a mere serpent.

Milton also gives us fascinating insight into Satan’s psyche. It’s not that he is just evil per se, or that he hopes to make himself feel better after his fall. As he puts it: ‘Nor hope to be myself less miserable by what I seek, but others to make such as I’. In that mindset, hell is wherever Satan goes. It’s a particularly miserable way of seeing the world and tearing everything down with you. In that way, we all possess the potential to become like Satan (yay).

Twain’s contempt for the human race

To leave the realm of drama and poetry and enter the world of prose, I’ll finish with Mark Twain. Unlike virtually all his other work, The Mysterious Stranger is incredibly dark, depressing and twisted, and casts a rather upsetting shadow over a writer otherwise known for adventurous and uplifting subject matters (while also exploring the problems of racism and slavery, of course).

The fragment actually exists in several attempts Twain wrote between 1897 and 1900 and features the story of three young boys called Theodor, Seppi and Nikolaus who live in an Austrian village (although some of the attempts are set in other locations).

Satan moves to the village and predicts a grim future. When one of his prophecies comes true, the boys ask him for assistance, but his help is generally less than merciful. In one case, for instance, he predicts a long disease-ridden period for one of the characters, and his act of mercy is to kill the boy immediately, thus preventing the period of suffering.

Twain’s Satan is so effective because he holds an absolutely detestable and grim view of the world. When he departs towards the end of the story, he leaves the boys with the words: ‘Here is no God, no universe, no human race, no earthly life, no heaven, no hell. It is all a dream – a grotesque and foolish dream. Nothing exists but you. And you are but a thought – a vagrant thought, a useless thought, a homeless thought, wandering forlorn among the empty eternities!’

Goethe’s and Marlowe’s Tempter

‘Hang on’, I hear you say, ‘didn’t you promise not to include Satan-like characters?’ Yes, I did; but I do consider Mephistopheles from Marlowe’s Dr Faustus and Goethe’s Faust Satan. He looks like him, talks like him, he’s a supernatural being. In other words, in every important way, Mephisto IS Satan.

‘Hang on’, I hear you say, ‘didn’t you promise not to include Satan-like characters?’ Yes, I did; but I do consider Mephistopheles from Marlowe’s Dr Faustus and Goethe’s Faust Satan. He looks like him, talks like him, he’s a supernatural being. In other words, in every important way, Mephisto IS Satan.

Also, these two may be the same character from the same story, but Goethe and Marlowe were different writers (duh) from different countries (double duh) who wrote in completely different time periods (tripe duh), so it’s difficult to do both of them justice at once. They’re both fascinating in their own way and both plays are absolutely excellent and need to be seen or read by anyone who’s interested in Satan (or literature, for that matter).

Nevertheless, in crucial ways they are identical, which is why I am putting them together. Both only appear after Faust summons them (meaning that we invite evil into ourselves), both are witty and eloquent, both act evil primarily through temptation, and both depict hell as being the absence of God (by which they mean the absence of everything that is good).

There are good reasons why the Faust story is so popular, and I believe everybody I’ve talked to said that Mephisto is their favourite character. He’s just fun, and anyone can understand how flirting with the devil to get personal pleasure and gain might be a tempting prospect. Of course, a real Mephisto is unlikely to appear if you summon him, but your life may feel like a real hell if you invite misery into your own home the same way Faust does in both ‘versions’ of this story.

Closing thoughts

As you can see, there are many excellent depictions of Satan in literature. Hopefully some of these will inspire you to go on your own treasure hunt for other depictions. Or even just to seek out these works if you didn’t know them before.

I believe part of the reason humans find Satan so fascinating is because of our own proclivity towards maliciousness. Given the right circumstances, anyone can become ‘evil’ and act in a way which inflicts suffering on other people. But it’s good to be aware of it. By exploring ‘absolute evil’ in literature we are able to warn ourselves of what the absolute worst can lead to.

Did you enjoy this list? Know of any other ones I should have included? Then please leave a comment. Otherwise, why not share this post? Then please click on one of the tender buttons below to share it on the social media of your choice.

Artists, too, never really discriminate in the same way that consumers do. Before capitalism guaranteed the emergence of the middle-class, it was very difficult to distinguish between popular and high culture – indeed, even Shakespeare first wrote and acted for a company dedicated towards entertaining ‘commoners’ in a dodgy neighbourhood. Only time (and his genius!) raised him into the ranks of ‘high’ culture.

Artists, too, never really discriminate in the same way that consumers do. Before capitalism guaranteed the emergence of the middle-class, it was very difficult to distinguish between popular and high culture – indeed, even Shakespeare first wrote and acted for a company dedicated towards entertaining ‘commoners’ in a dodgy neighbourhood. Only time (and his genius!) raised him into the ranks of ‘high’ culture.  There’s not really any way around it. To avoid both pitfalls, all I can recommend is to be more open-minded about things. Why would you bother condemning

There’s not really any way around it. To avoid both pitfalls, all I can recommend is to be more open-minded about things. Why would you bother condemning

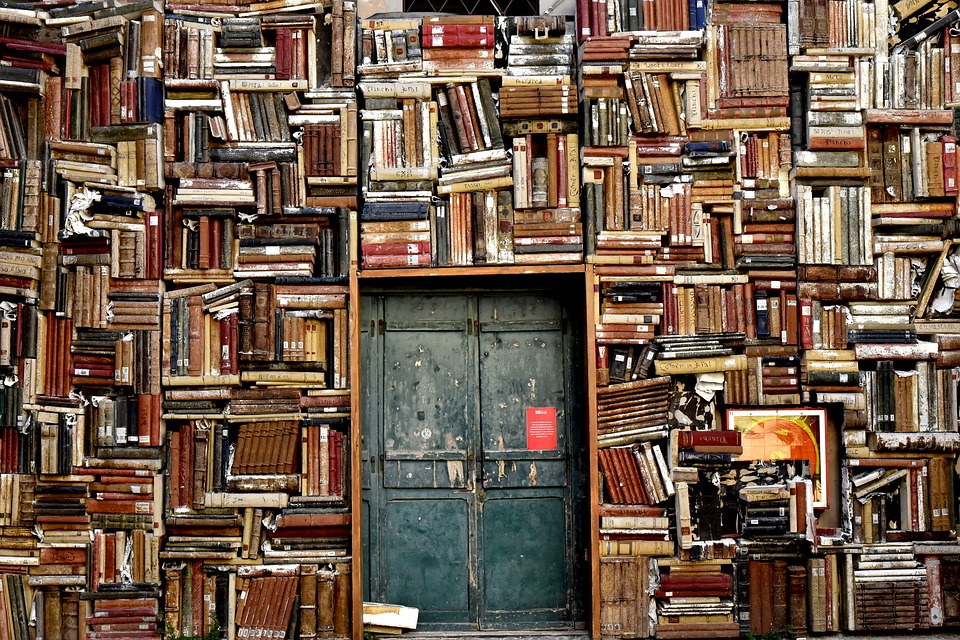

Lastly, the atmosphere in 2nd-hand bookshops feels a lot more homely than in traditional book stores. You may meet interesting people who share your love of the written word. The shopkeepers are usually truly passionate about what they do, and chances are you’ll discover a volume that has been out of print for many years, making a trip to one a unique experience.

Lastly, the atmosphere in 2nd-hand bookshops feels a lot more homely than in traditional book stores. You may meet interesting people who share your love of the written word. The shopkeepers are usually truly passionate about what they do, and chances are you’ll discover a volume that has been out of print for many years, making a trip to one a unique experience.