Writing an essay on a given topic – whether for school, university, or for any other reason – can often feel overwhelming. There are just too many things to keep in mind; too many things to pay attention to. These tips should give you a head-start in kicking off your next essay project.

So, you’ve figured out how to read poetry. You’ve understood the ins and outs of metre. You might even have considered a range of material to write about. But the idea of turning everything into a fluent essay immediately stops you in your tracks. What to do?

It’s true that many students see essay-writing as a stain on their experience at university. As that one annoying thing they have to do besides reading and enjoying themselves. To them, it often just seems like the necessary evil on the pathway towards a degree.

And it’s completely understandable. After all, anything which is assessed and can mean either pass or failure is sure to paralyse anyone’s enthusiasm. But it doesn’t have to be that way. To assist you in your essay-writing endeavours, I’ve compiled a list with several tips you can do to ensure you not only succeed in writing good essays but perhaps even enjoy writing them.

Why not a step-by-step guide?

The problem with step-by-step guides is twofold. First, every writer works differently, and second, every topic is different. Exact guidelines on how to approach each essay are therefore not only less useful than you might think, but can even be rather counter-productive.

In terms of student individuality, some people like to do complete their research entirely before writing. Others like to write while researching. Others write a complete draft just containing their own ideas before they then fit the research around it. A step-by-step guide would assume that you work exactly the way I do.

In terms of topic individuality, there are also huge differences. When writing on poetry, for instance, you might wish to focus largely on a close reading of the text. When discussing primarily (literary) theory, the amount of secondary literature might be greater. Again, a concise guide on how to write an essay might not take differences into account.

Use guidebooks – but very sparingly

If you’re a particularly industrious student, you may consider buying some guidebooks to help you in your essay-writing endeavours. After all, why not? There are many good ones out there, such as How to Get a First, First Class Essays or the Study Skills Handbook.

But after having read some of them myself, I would strongly urge you to limit yourself to one or two at the most. They often contain some really good general advice, but other than that, a lot of their general material is just common sense – such as grammar rules, common mistakes, and yes, often step-by-step guides.

Ideally, you should pick up a lot from these books during the first year at university, and just buy one for reference. It’s probably wiser investing your time in trial-and-error, rather than reading more or less the same material over and over again.

Select the right topic

If you’re at school, you may think this is a bit of a downer. One of the big differences between A-levels and university is the privilege of being able to choose your own topic. But even if you don’t have that liberty, it’s no reason to despair – most topics do actually get more interesting than they seem to be at first sight, and teachers try to nudge you towards a better understanding. Looking into your essay diligently and researching well may put you leaps ahead of everyone else, allowing you to understand really difficult stuff and enjoy the work a lot more.

If you’re at school, you may think this is a bit of a downer. One of the big differences between A-levels and university is the privilege of being able to choose your own topic. But even if you don’t have that liberty, it’s no reason to despair – most topics do actually get more interesting than they seem to be at first sight, and teachers try to nudge you towards a better understanding. Looking into your essay diligently and researching well may put you leaps ahead of everyone else, allowing you to understand really difficult stuff and enjoy the work a lot more.

If you do have the privilege, you may find that, without a doubt, selecting the correct essay topic or question is the single most important thing to do before you start. It takes a lot more responsibility since you’re in charge of your own degree of understanding the subject matter. No matter what you think your lecturer would like to read most, there’s actually only one way to go about it: choose something you enjoy.

It seems to be a fundamental psychological issue. Work unrelated to our own interests generally doesn’t motivate us, so only by writing about something you actually enjoy will you be able to motivate yourself, in the long run, to do well. After all, you’ll be spending a great deal of time researching your topic. If it puts you to sleep, how can you expect to be concentrated all the time?

The same thing can be said for the selection of your essay question. If it’s bland, obvious or has been done before, you may struggle to work with it efficiently. Instead, choose an interesting one and mould it in the direction you wish to go. At university level, most questions are posed in a way which allows you to alter them ever so slightly and do what you’ll enjoy.

Flow with your guts, not with the stream. Your teacher is more likely to give you a good mark if you’ve done your own topic well than if you half-heartedly produced something which happens to take the currently popular perspective on any given text. Do what feels right to you, not what academia currently considers ‘in’.

Know where to find research material

You’d be surprised how many students struggle to find the right material. But in our day and age, that needn’t be the case. Libraries, as I noted elsewhere, are an excellent go-to place for books. For academic purposes, obviously use academic libraries (such as the Senate House in London).

But with the internet, you may not even have to leave your room to do your research. You should probably be able to find most things online if you know where to look. Academic indexes are the best resource you have since they often provide material from journals for free (provided you have academic access from your university).

Google Scholar is an obvious one. Personally, I’m also a great fan of JSTOR and muse. DOAJ is probably the most advanced open access index out there with a focus on research journals, and OAPEN has an excellent open access book collection. It may take you some time to work out the best way to find the most useful texts, but once you’ve mastered your index of choice, you will find an almost limitless supply of essay inspiration.

Google Scholar is an obvious one. Personally, I’m also a great fan of JSTOR and muse. DOAJ is probably the most advanced open access index out there with a focus on research journals, and OAPEN has an excellent open access book collection. It may take you some time to work out the best way to find the most useful texts, but once you’ve mastered your index of choice, you will find an almost limitless supply of essay inspiration.

There are, of course, many more, and some subject-specific ones (PMC for medicine or PsycINFO for psychology, for instance). It’s always good to be aware of any indexes out there and to figure out how to use them. When in doubt, ask your lecturer which services they tend to use.

Work efficiently and reward yourself

You probably know the type. Or are of the type yourself? Those who are so undisciplined that they force themselves to go to the library each day – and end up spending their time there watching YouTube videos or browsing social media.

The truth is, many students work inefficiently and just go to the library to calm their conscience and to claim they’re working all the time. In reality, it shouldn’t matter too much where you work, as long as you are actually working. Of course, this is difficult to do.

Try to set up your own work-reward system. Promise yourself a reward if you work concentrated for a certain amount of time. Don’t reward yourself if you don’t meet your goal. And take regular breaks in-between to maintain concentration – say, one hour of concentrated reading and then 10 minutes of social media as a reward.

Don’t start too late

There’s no excuse for this one. You know the reading list in advance and the questions are usually handed out just after reading week. The number of students who still don’t start work on their essays until much later – around Christmas or Easter – is insane.

By (efficiently) working on essays you’re already studying better than you would when just looking over your notes repeatedly, so why not use your ‘regular’ revision time for essay work? That way you won’t end up with too little time and have more time to enjoy yourself during the holidays.

Also, that way you’re motivating yourself because you begin to accumulate tangible results during the ongoing academic year. Not to mention that your nerves will thank you as well since you avoid the stress of last-minute essay-writing entirely.

Look after yourself

If you follow the advice of the previous two points, you’ll end up with much more time for personal pleasure than before – so use it to look after yourself. No more overnight work for last-minute essays. You’ll have plenty of time to sleep soundly and eat healthily.

If you follow the advice of the previous two points, you’ll end up with much more time for personal pleasure than before – so use it to look after yourself. No more overnight work for last-minute essays. You’ll have plenty of time to sleep soundly and eat healthily.

You’ll also have a better conscience when enjoying yourself. Worked hard all week? Then there’s no reason not to go to a club, to a concert, to play a game, to read a book for pleasure. If you work efficiently and look after yourself, you’ll have a much better work-life balance.

Write well

There’s nothing more annoying than yet another essay which is written in essaynese rather than English. It’s a dreadful trend – all of the conventions in essay-writing stifle any form of creativity the medium ought to have. Anything along the lines of stupid phrases (‘In this essay, I would like to…’) to unnecessarily complex words fall under this category.

Why not, instead, try to write well? Obviously not with colloquial language, but good language which you’d still not be afraid to use every day. Write clearly, concisely, and try to make sense in what you write. Never go overboard with words nobody would ever use. A well-researched essay doesn’t need them, and it might even leave the impression that you’re hiding a bad argument behind confusing language.

This doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t use technical terms correctly – of course you should. But it does mean that you should avoid stifling your own expressive power by writing in a way which just seems to scream ‘I’m clever’ and more likely than not will annoy your examiner.

Think

In-between all the research, planning and writing, it’s surprising how many students forget to take their time to think actively about their project. But it’s during active thinking that many of the best ideas come about, so actually putting time aside for this is a great way to push forward your argument.

I think the reason so many fail to do so may be related to the feeling of not doing anything. You’re not jotting down notes, you’re not putting pen to paper – so it seems like a waste of time. But in reality, without actually stopping to grasp what your thoughts on your topic are, chances are you’ll just reproduce the ideas from secondary sources.

Consequently, I’d recommend that you really do take it slowly and think actively about what you’ve just read, what you’ve just written, and look closely at the text you’re analysing – ideally word for word if you’re hooked enough to do so.

Structure your essay, but be flexible

If you’re still at school, you sadly will have rather clear-cut structures when it comes to your essays. At university, you definitely shouldn’t maintain the formulaic methods you learned at school, but you do still need to have some structure (and if it’s the result of inventing one of your own). Anything goes, really. The thing is, it has to make sense for your topic.

If you’re still at school, you sadly will have rather clear-cut structures when it comes to your essays. At university, you definitely shouldn’t maintain the formulaic methods you learned at school, but you do still need to have some structure (and if it’s the result of inventing one of your own). Anything goes, really. The thing is, it has to make sense for your topic.

In the end, an essay has to make one central argument. And to convince your readers of your argument, your essay needs a structure which builds towards it. Everything should add to the argument and demonstrate that you’ve thought it through.

But also don’t be afraid to be flexible. If things aren’t working out the way you thought they would, add a different point, or cut something out. Or shift things around a bit. The trick is to find the ideal structure for the topic at hand that you’re working on.

Closing thoughts

These are just some of the general pieces of advice I’ve picked up after 4 years of studying a subject in the Arts & Humanities. No doubt there is much more to learn, but that’s essentially why you’re at school or university– to perfect the art of writing an essay.

Can you think of any other tips one might add? Anything you disagree with? Then please leave a comment. Otherwise, if you enjoyed this post, why not share it on the social media of your choice? Then click on one of the tender buttons below.

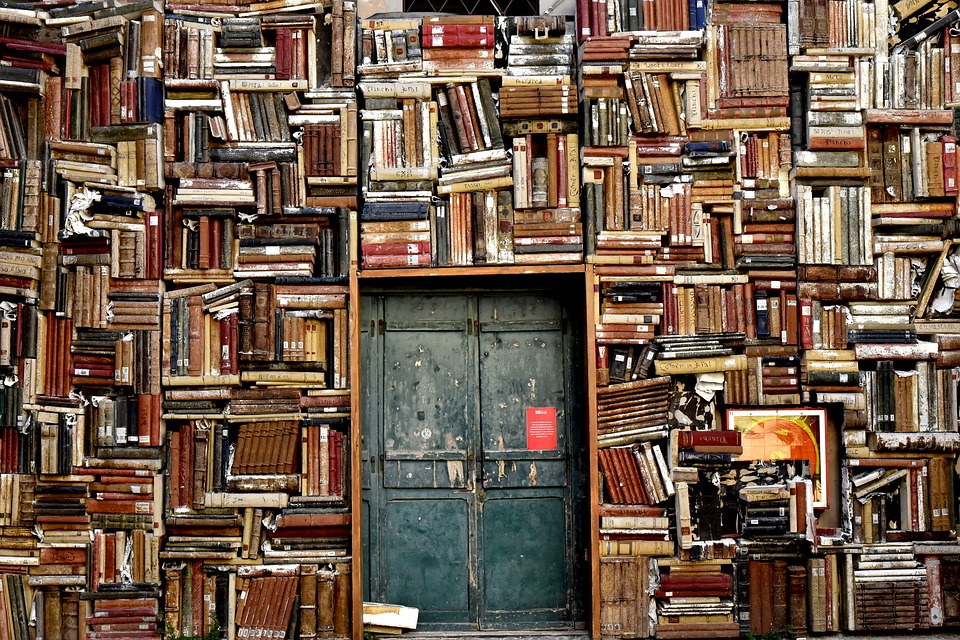

Lastly, the atmosphere in 2nd-hand bookshops feels a lot more homely than in traditional book stores. You may meet interesting people who share your love of the written word. The shopkeepers are usually truly passionate about what they do, and chances are you’ll discover a volume that has been out of print for many years, making a trip to one a unique experience.

Lastly, the atmosphere in 2nd-hand bookshops feels a lot more homely than in traditional book stores. You may meet interesting people who share your love of the written word. The shopkeepers are usually truly passionate about what they do, and chances are you’ll discover a volume that has been out of print for many years, making a trip to one a unique experience.

The beautiful St Pancras Old Church, on the other hand, is ancient – and rather small. As the newly built up areas around St Pancras, especially near Euston Road, were beginning to boom, the parish quickly decided that it was time for a larger church, so in 1816 they began building the new St Pancras Church.

The beautiful St Pancras Old Church, on the other hand, is ancient – and rather small. As the newly built up areas around St Pancras, especially near Euston Road, were beginning to boom, the parish quickly decided that it was time for a larger church, so in 1816 they began building the new St Pancras Church. The Hardy Tree, one of the Great Trees of London, is probably the most spectacular of sites to visit if you happen to go to the churchyard. The large ash tree’s roots partially reach out from the soil, forming their way through a pile of neatly arranged headstones surrounding it, making both rock and wood an intricate part of each other.

The Hardy Tree, one of the Great Trees of London, is probably the most spectacular of sites to visit if you happen to go to the churchyard. The large ash tree’s roots partially reach out from the soil, forming their way through a pile of neatly arranged headstones surrounding it, making both rock and wood an intricate part of each other.